In October, 1956, Gene met Nicole Wable in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Nicole, a native of Montreuil-sur-mer, France, was visiting friends she had made as a graduate student studying English Literature as a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville in 1953 - 1954. Finding connection and affection immediately, Gene knew he had to stay in touch with Nicole even though she was returning to France. The two continued to exchange letters. Their romance grew and Gene proposed to Nicole through handwritten letter. Gene and Nicole were married in 1957 in France. After the wedding, they lived in Conway where Nicole became a professor of foreign language at UCA. They had three children, Hadrian, Marc, and Mathilda, who were raised to speak both French and English - and to value both good art and a good French meal.

During Gene’s teaching career, the family visited France almost every summer, staying in a home Nicole inherited in Le Touquet in Pas de Calais, France, which they named “Phare Corner.” The term means lighthouse in French, and served as a play on words, as the home stood on a corner in the shade of a lighthouse in what was to them far away France.

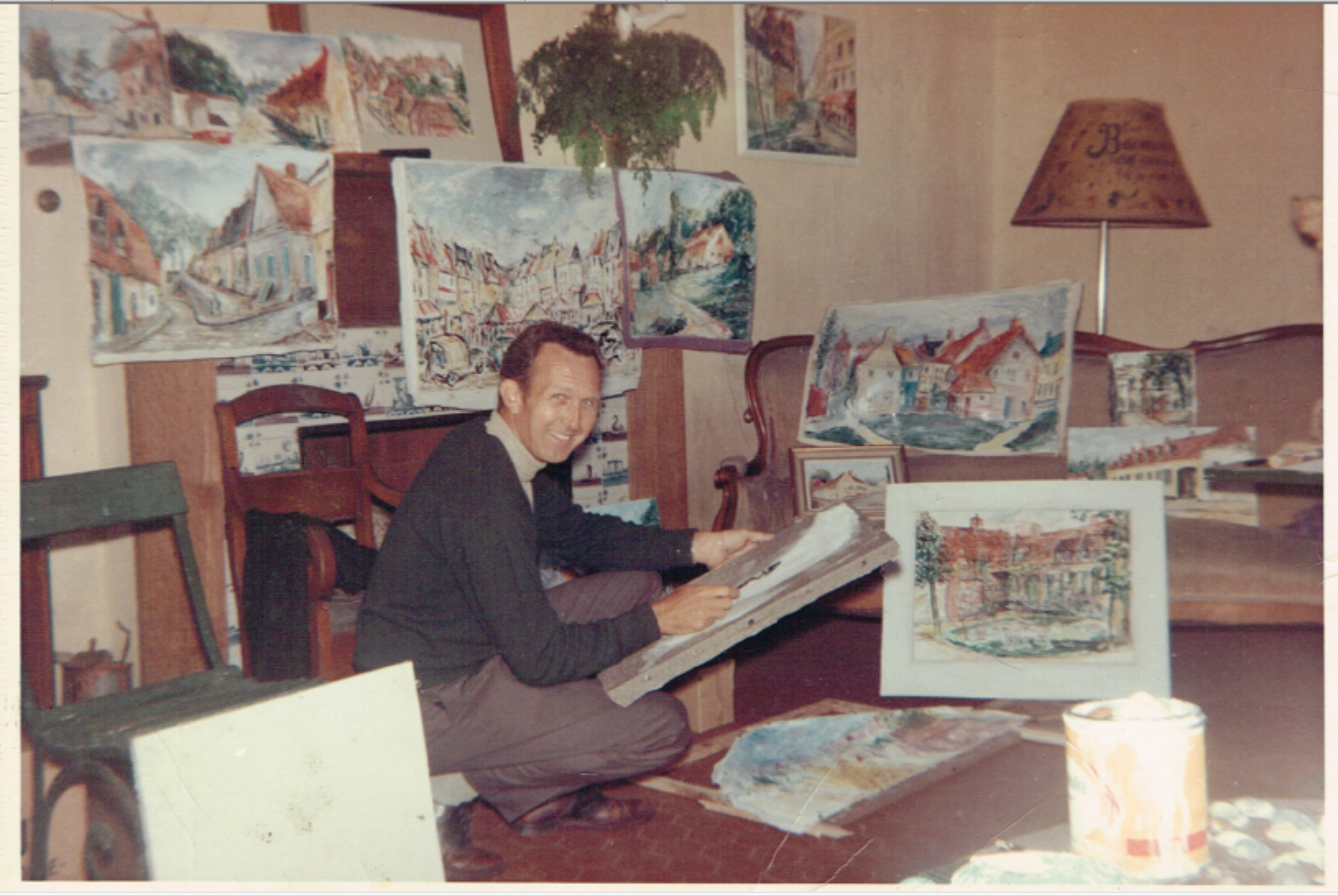

While in Europe, Gene studied with noted French (American born) surrealist Henri Goetz in Fontainebleau and Paris. He also studied with Leo Marchutz in Aix-en-Provence, the German painter, lithographer, and foremost authority on the work of Paul Cézanne. Impressionists such as Cézanne, Henri Matisse, and other traditional late-nineteenth-century figures influenced Gene’s style and color palette, and Gene learned to work in the method of French Painter Raoul Dufy at the request of Marchutz. Later, Gene studied at the Fuller Art Studio in Saint Ives, England under the school's founder, portrait and still life painter Leonard Fuller. These experiences broadened his style, process, and identity as an artist. He would return from his travels in France to Conway, Arkansas with insights into a faraway world and the interesting people in it - and stacks of watercolors telling stories of his travels.

While in France, Gene was awarded medals in local art competitions, and some of his work hangs in the Musee d’Art Le Touquet as well as with local collectors. The French countryside, seascapes, and villages inspired Gene’s artwork, as did the picturesque streets and sidewalks of Paris. As an accomplished watercolorist, he made hundreds of beautiful paintings on location, depicting scenes of urban and rural life in post-war France and other parts of Europe, capturing the essence of the space and time around him.

As the family explored the French cities and countryside, Gene often pulled over in the middle of a trip to create a watercolor on site - despite any rumblings from his 3 young children. The striking beauty of France existing within the ordinary daily lives of the residents inspired him to create works at any given moment, in any given location. Gene's watercolors capture more than a photograph could, they display the essence and the energy surrounding him at the time, serving as both a journal and a photo album of the French lifestyle.

Not only was Hatfield a talented artist, he was driven, prolific, and deeply committed to creating art. As an artist, teacher, and willing collaborator, rare was the day Gene was not spending his creative energy in the pursuit of making art. He worked tirelessly and quickly, creating well over one thousand pieces of art in an impressive variety of media and styles. The hundreds of watercolors Gene painted on location throughout northern France were delicate but not dainty, and bold in their exaggerated colors and perspectives, capturing the feel-of-place as much as the images of what he saw. Hatfield also worked continually in oil, pastel, acrylic, and mixed-media, and he created three-dimensional works in clay, wood, stone, plaster, metals, and found objects. His yard was an ever-changing exhibit of sculptures assembled from all manner of discarded material, often collected from waste bins of the local factories. Conway's industrial base at the time included factories making school busses, shoes, chairs, pianos, and other items that created the perfect stream of waste material Gene could use for his outdoor sculptures. He often incorporated those materials in his yard-art for the very purpose of demonstrating his concern for the impact of mass consumerism on society and the environment.

As a university instructor of Art Appreciation, Hatfield was continually studying the art movements of the times, and happily worked in styles including impressionism, surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism. He was comfortable working in various media and styles and incorporating aspects of the contemporary movements of his time into his art. But, as a nonconformist at heart, he was continually exploring on his own, beyond the limits of any particular movement. His lifelong passion was simply to make art, and his only stated regret at the end of his life, despite the impressive number of his creations, was that he "wished he had created more art". He was reassured by those around him that he had done quite well in that category.

The impermanent nature of Gene's Yard Art, which he changed almost daily, did not allow much of it to survive time and the elements. But twentythree of his works are permanently registered as part of the Smithsonian Institution's Save Outdoor Sculpture program. Some of the more lasting outdoor sculptures are part of the Hatfield family's extensive collection. Gene showed very little interest in selling his works during his lifetime, except for the occasional sale to friends and acquaintances. He also donated works to various causes and organizations, and left his surviving family a great volume of paintings and three dimensional work, including hundreds of beautiful watercolors documenting the villages, farms, beaches, and Paris streets captured in plein-air by his unique eye, often while his wife and children picnicked and played nearby.